Introduction

The Great Migration

The Race Riot of 1919

Aftermath and Legacies

Why It Matters Today

Historical Photos

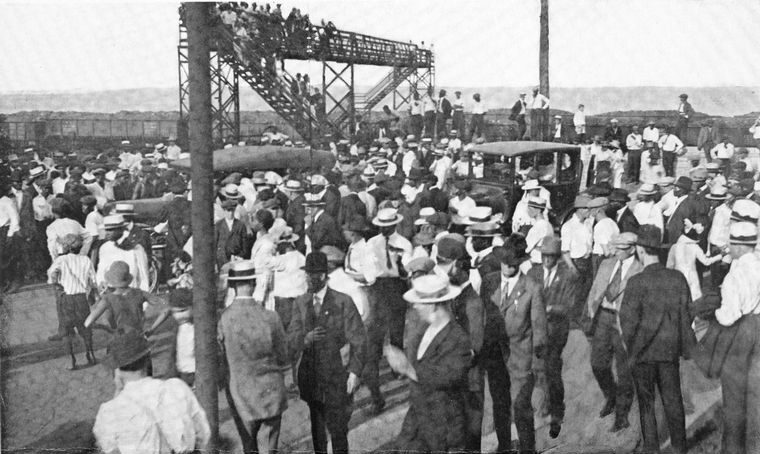

The Race Riot of 1919

On Sunday, July 27, 1919, an unusually hot summer day, Black seventeen-year-old Eugene Williams and four of his friends took a homemade wooden raft out into Lake Michigan on the South Side. They pushed off from 26th Street beach, the only beach in the city reserved for Black beachgoers and swimmers. Although there was no legal segregation in Chicago, de facto segregation was common including along the Lakefront. While in the water the boys unintentionally floated across an invisible boundary line demarcating a “whites only” part of the lake as well as the beach, at 29th Street.

George Stauber, a twenty-four-year-old white man, hurled stones at the five Black boys until Williams, ultimately, drowned. The white police officer at the scene, Daniel Callahan, refused to take Stauber into custody, nor would Callahan let a Black police officer do so. Subsequently, a crowd of Black and white Chicagoans gathered in protest near the beach. Police reinforcements massed at the scene but confronted the Black crowd rather than investigating Williams’s murder. As police acted more aggressively towards the crowd, a Black man named James Crawford fired a gun at the officers. Police returned fire and killed Crawford.

As word and rumors spread, the city erupted in racial violence. Much of the rioting took place on the South Side in the Black Belt and in nearby white ethnic neighborhoods like Back of the Yards and Bridgeport, though violence also spread northward to the downtown Loop area as well as the near West Side. White males, especially members of youth gangs and so-called “athletic clubs,” loaded into automobiles and sped through Black neighborhoods, firing indiscriminately at African Americans and their homes. Some of these gangs also set fire to tenement buildings inhabited mostly by Eastern European immigrants in order to stoke further tensions between working-class white communities and Black Chicagoans. White mobs pulled African Americans from streetcars and attacked individuals walking to and from work, severely beating, and on several occasions, killing, their victims

As whites attacked, however, Black people, and in particular World War I veterans, fought back in unprecedented numbers by returning fire or otherwise engaging in self-defense: a street-level expression of the growing race consciousness catching fire across the country that summer. This spirit of resistance was famously captured in the Jamaican-born, Harlem-based writer Claude McKay’s poem “If We Must Die,” published in the socialist magazine The Liberator as a response to the race riots of the Red Summer. In Chicago, the National Guard was finally called in to quell the violence and to bring much-needed provisions into the besieged Black Belt but, eventually, a steady rain proved most effective in restoring peace.

Over the course of one week, thirty-eight people were killed—twenty-three Black and fifteen white—and some 537 Chicagoans were injured. Two-thirds of those injured were Black, and yet African Americans also made up two-thirds of the 138 persons indicted for riot-related crimes by the State’s Attorney’s office. Ultimately, the Chicago Police Department and the State’s Attorney’s office overwhelmingly blamed Black resistance for the violence and largely ignored or defended white perpetrators.