On Saturday, July 22nd, CRR19, in partnership with Organic Oneness, will host its fifth annual commemoration of the events of 1919 and, once more, will feature a historic bike tour. Please register here for the event. Our 2-hour tour explores some of the history of the Chicago race riots of 1919 and its legacy of residential segregation (arguably, its “origin story”) as well as highlighting the resilience of the Black community and its bold resistance to racism and racial violence. This tour will include the unveiling of some of the markers commemorating some of those killed, created by Chicago’s own Firebird Community Arts. The tour travels through parts of Bronzeville and Bridgeport, exploring the histories of Black migration, struggle, and institution-building that contributed to the development of Chicago’s Black community. Participants will also learn about the forms of anti-Black racism and segregation that have shaped the development of race relations on the South Side, from 1919 through the present. Please register here for the event! This map shows the eight stops of the tour.

The "Vortex of Violence"

Our tour begins at 35th & State, which was labeled the “Vortex of Violence” the Chicago Defender, because it was the epicenter of the violence that engulfed Chicago for a week in the “Red Summer.” The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 remains the bloodiest episode of racial violence in the city’s history. 38 people were killed, 537 were injured, and more than a thousand left homeless in nearly a week of mass violence across large parts of the city.

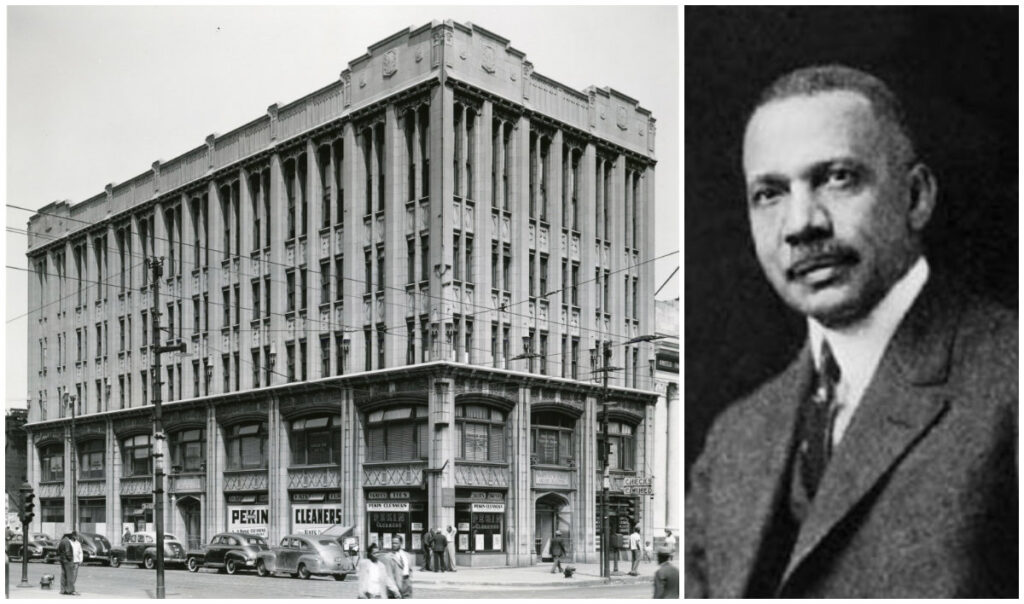

Jesse Binga was Chicago’s first Black banker and an icon of Black entrepreneurship in the 1910s and 20s. Located on the west side of State Street at 35th Street, Binga’s Bank provided a welcome alternative to the large white-owned banks and the predatory lenders who exploited African Americans seeking to purchase homes and establish businesses. Binga’s success made him a frequent target of white racist violence, and both his personal home and business were bombed before, during, and after 1919. Here, we tell the story of the rise and fall of Jesse Binga, the Arcade Building he built, and the “State Street Stroll,” at the heart of the Black commercial and entertainment district.

Chicago Defender

Our next stop is The Chicago Defender building, which housed the famous newspaper from 1920 until 1960. Founded in 1905 by Robert Abbot, the Defender became an influential voice in the African American community, leading the struggle against lynching, unequal housing, disfranchisement, and other forms of racial discrimination from the early 20th century onwards. On this stop we explore the role of the Defender in promoting the Great Migration, which set the stage for a new era of struggles for racial equality, as well as new forms of racist backlash, in Chicago.

Pilgrim Baptist Church

Pilgrim Baptist Church is historic for many reasons including because Dr. Thomas Dorsey, the “father” of gospel music, worked here for many decades. This congregation was founded in 1917 and operated in several different parts of what is now called Bronzeville before moving to this building in 1922. Originally built for the Kehilath Anshe Ma’ariv Synagogue and opened in 1891, it was designed by famed architect Louis Sullivan and engineer Dankmar Adler with the initial drawings prepared by draftsman Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1932, Thomas Andrew Dorsey became a member of the church and organized the “Pilgrim Baptist Church Gospel Chorus” at the request of Reverend Austin, Sr. Under Dorsey’s direction, some of gospel music’s most legendary singers performed including Mahalia Jackson and Sally Martin (Queen of Gospel). The Staple Singers also sang here and Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke here several times. A devastating fire occurred in 2006 and the church moved across the street, where it still resides. This building eventually will become the National Museum of Gospel Music.

Armour Square Park

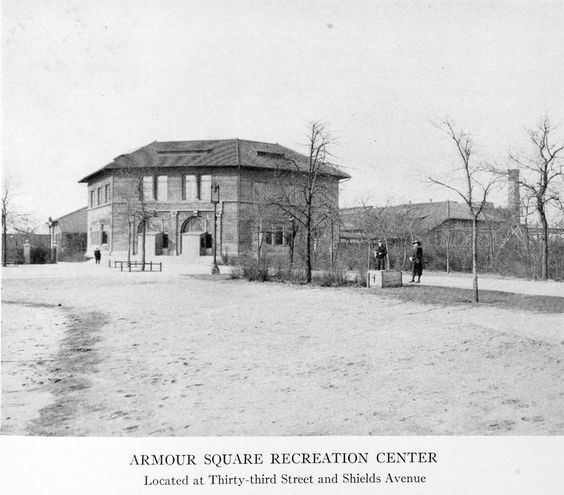

Our next stop is Armour Square Park, on the eastern edge of Bridgeport. Just to the east of the park is Wentworth Ave. which historically served as an unofficial dividing line between all-white Bridgeport and the Black community of the “Black Belt” (now called Bronzeville). Philip D. Armour, the wealthy head of a meatpacking corporation, donated the land for this park in 1906. Since then, the park has been a flashpoint in the city’s history of racial violence and segregation. Using Armour Square Park, we will discuss how the unofficial but very real racial borders of our city have been enforced, including by the white ethnic so-called “Athletic Clubs” and, later, by infrastructure such as the Dan Dyan Expressway completed by Mayor Richard J. Daley in 1962; Daley himself was a member of the Hamburg Athletic Club which was a key instigator of the violence in 1919.

Union Stockyard Gate

As far back as the 1860s, Chicago was the capital of US meat production and remained so into the 1950s. The heart of the country’s meatpacking industry was in Canaryville, a part of Bridgeport. In the WWI era, as many as 100,000 people worked in the yards and they hailed from a great many different ethnic communities. Although the work was dangerous, hard, and poorly-paying, generations of European immigrants found jobs in the yards. Notoriously, (white) employers refused to hire Black workers except sometimes to break strikes. However, WWI created to an unprecedented, huge labor shortage, resulting in employers started hiring Black men and women for jobs in the stockyards which became the largest source of employment for Black Chicagoans.

Roberts Temple

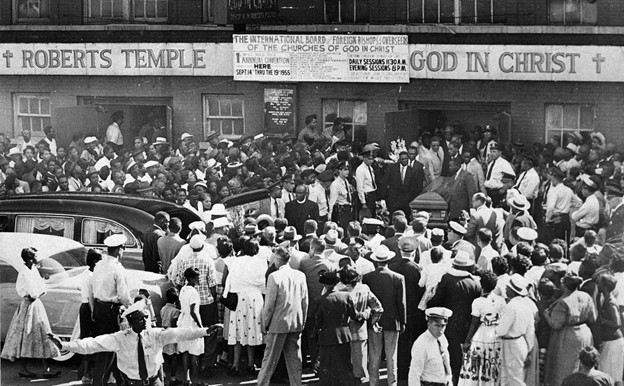

Our next stop is the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ. This historic building is the first Chicago sanctuary of this Pentecostal denomination with roots in early 20th century Memphis. Here we will explore the history of this important religious and cultural institution of Black Chicago, including the electrifying performances of congregant Sister Rosetta Tharpe (“godmother of rock n’ roll”) and Mamie Till’s bold decision to hold an open casket memorial service for her 14-year-old son, Emmett, who had been brutally murdered while visiting family in Mississippi in 1955.

Ida B. Wells Monument

Our next stop is the “Light of Truth Ida B. Wells National Monument,” crafted by legendary Chicago artist Richard Hunt and dedicated to the memory of the great anti-lynching activist, Ida B. Wells-Barnett. We will tell the story of her pioneering efforts to document and critique systemic anti-Black violence in Memphis, Chicago and across the U.S., including during the Chicago riots of 1919. We will also discuss the construction and eventual demolition of the Ida B. Wells homes in this part of Bronzeville as well as the efforts to commemorate Wells’ legacy in present day Chicago.

Victory Monument

Our tour will conclude at “victory,” that is the Bronzeville Victory Monument at 35th and Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive. This monument was constructed to honor the 8th regiment of the Illinois National Guard, an all-Black Army unit renamed the 370th Infantry during World War I. Following this stop, we’ll return to our starting point in the IIT parking lot next to the CTA Green Line station, 35th and State streets.