Introduction

The Great Migration

The Race Riot of 1919

Aftermath and Legacies

Why It Matters Today

Historical Photos

Aftermath

The devastation wrought by the 1919 Chicago Race Riot was terrible, and so was the aftermath along with the Riot’s subsequent expulsion from official memory. Not only had hundreds been killed and injured, large swaths of property in working-class Black and white neighborhoods on the South Side also had been destroyed: one thousand Black families were left homeless. Some major employers—like the stockyards—temporarily closed during the Riot, leaving many workers without work or access to back pay. When the meatpacking plants reopened, some plant owners banned African Americans from returning to their jobs for fear of further clashes with white workers, which exacerbated the unemployment crisis.

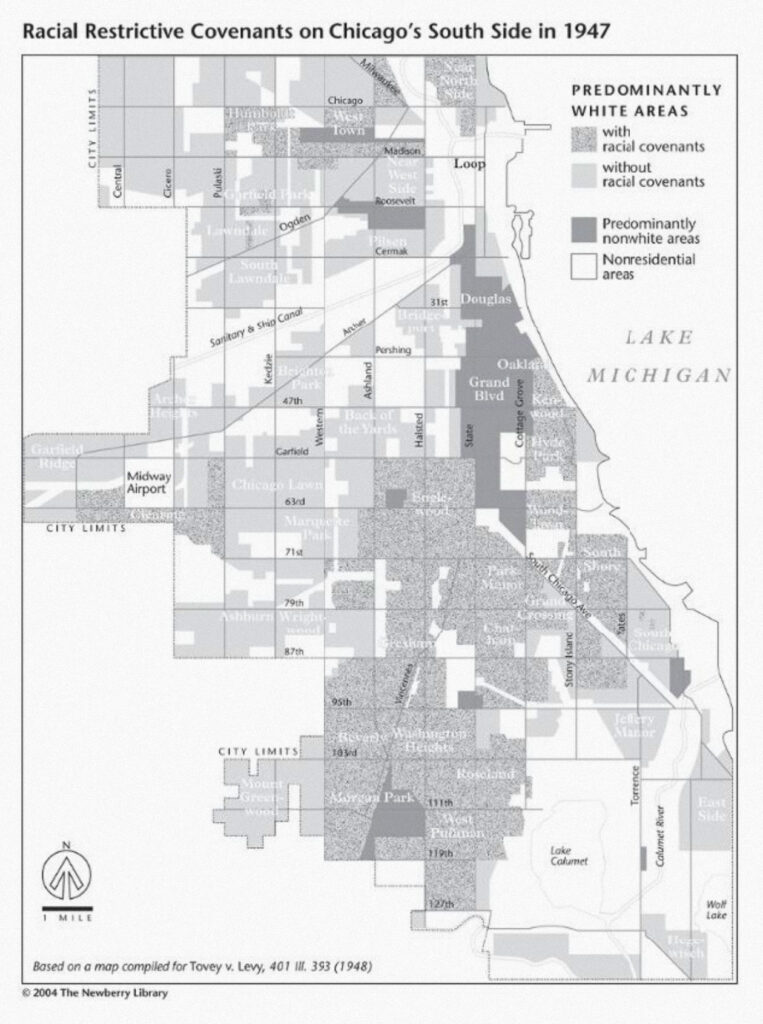

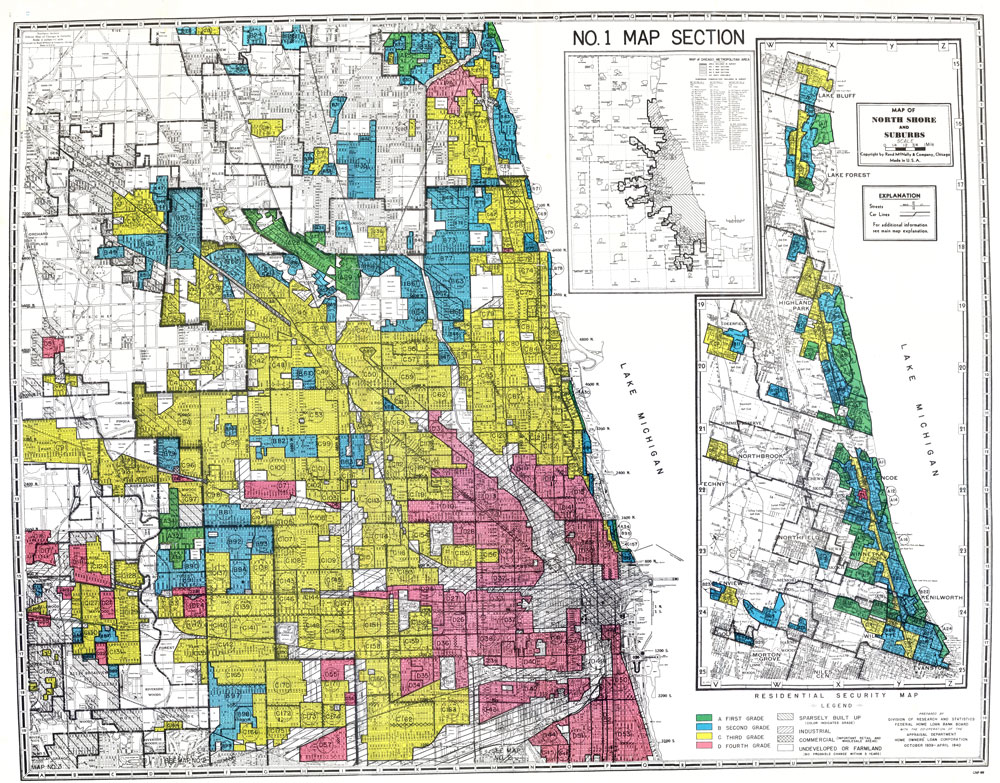

Civic leaders also lacked the funds and the will to prosecute most rioters. Only a handful were ever tried or saw any prison time. Most of those prosecuted were Black: there were just twenty-one total indictments, seventeen Black and four white, and five total convictions, three Black and two white. Law enforcement and local elected officials shielded the white men who committed most of the riot’s violence. Many South Side white politicians sponsored local “athletic clubs,” or youth gangs, that ultimately were found to have instigated much of the violence. Future mayor Richard J. Daley later became president of Bridgeport’s Hamburg Athletic Club, one of the clubs implicated in the Riot, though he never confirmed or denied personal participation in the violence. Ultimately, some of Chicago’s white political and economic elites dismissed the Riot as the work of the city’s lower-class elements, both white and Black, who they claimed lacked education and morality. It was in the best interests of decent people, they argued, to separate these whites and Blacks to avoid future trouble. Such conclusions paved the way for racist policies like the implementation of racially restrictive covenants and redlining which prevented Black Chicagoans from buying homes in certain neighborhoods

The Report of the Chicago Commission on Race Relations, 1922.

Carl Sandburg’s foundational work on the Chicago Race Riot, 1919.

In August of 1919, Illinois Governor Frank Lowden called for an investigation of Black life and race relations in the city of Chicago. The resulting twelve-person Chicago Commission on Race Relations was made up of prominent Black and white Chicagoans and represented an extraordinary effort at interracial collaboration, research, and resolution. African American sociologist Charles S. Johnson carried out most of the research.

The resultant six-hundred-plus-page report, published in 1922 and entitled The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot, remains a landmark of sociology. It covered the Great Migration, housing, employment, and social life for African Americans in Chicago, the causes and aftermath of the Riot, and surveys on public opinion regarding the city’s “race problem.” The Report extensively detailed the Commission’s findings of systemic racism in housing and employment policy, and the Commissioners ultimately provided recommendations to remedy these problems. Many of their prescriptions would have required active support and participation from the Chicago Police Department, the State’s Attorney, and local politicians, all of whom the Commissioners charged with exacerbating the violence of the Riot or failing to apprehend white perpetrators. The report’s reasonable recommendations went unheeded. A century later, many of them appear shockingly relevant and still needed.

Legacies

Whether or not we remember the Chicago Race Riot of 1919, we live with its legacies. The immediate aftermath of the riot laid the foundation for decades of racist policies aimed at containing Black Chicagoans . In the 1920s, city government and industry embraced legal strategies to segregate Black people. Racially restrictive covenants barred Black Chicagoans from renting or owning residences outside of a small number of neighborhoods. Celebrated writer Lorraine Hansberry based her 1959 play, A Raisin in the Sun, on her family’s experience battling a racially restrictive covenant in the Woodlawn neighborhood on the South Side.

In the 1930s, these covenants became one of a much broader set of policies enacted by governments and industries across the country to create and maintain segregation. This is often described under the general term “redlining,” after the red lines used on financial maps to outline communities of color as “low property value” and not worthy of investment. In the 1950s and 1960s, federal highway projects magnified the effects of redlining, razing neighborhoods and deepening segregation by cutting off communities of color from other areas of the city. These policies and practices increased inequality in housing, education, and employment. Most white Americans supported these policies, either by actively participating or by doing nothing to change them.

Throughout the 20th century, structural and individual violence reinforced segregation. As it did during the 1919 riot, this reinforcement included heavily policing Black neighborhoods and incarcerating Black people while ignoring white racist violence. Resistance was met with more force. In 1969 the Chicago Police Department, working with the FBI, assassinated Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party and founder of the multiracial, socialist Rainbow Coalition, which brought together anti-racist radicals from Chicago’s Black, Latinx, and working-class white communities. Hampton was at home asleep next to his pregnant girlfriend when he and fellow Black Panther Mark Clark were murdered by the CPD. Hampton was just 21-years old.

Dismantling racial segregation in the U.S. is an ongoing struggle. We live with segregation’s long-term consequences, including current versions of structural racism and the persistence of white supremacist violence. Chicago remains one of the most racially segregated cities in the U.S. Bank lending practices in the city have created a modern form of redlining. In the past decade, the city government targeted Black and Brown neighborhoods for mass school closures. Communities of color, especially Black communities, continue to face police violence.

We also live with the legacies of resistance from the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. Across the city and the country, people continue to fight for equity and remember the past in order to create new futures.